Let's get straight to it. When you get a Schedule K-1, the first thing people usually look for is where to put the number from Box 1 (Ordinary Business Income). Most of the time, that income finds its home on Schedule E, which then feeds into your main Form 1040.

But that's just the tip of the iceberg. A K-1 isn't a single data point; it's a financial snapshot from a partnership, S corporation, or trust. Think of it as a summary of different types of income—from capital gains to interest—that need to be reported on specific, separate parts of your tax return.

Mapping Your K-1 to Your Personal Tax Return

Getting a Schedule K-1 in the mail can feel like being handed a puzzle without the picture on the box. It’s not just one number you can plug into a single line. Instead, it’s a detailed financial summary that you have to carefully take apart and reassemble across your Form 1040. If you misinterpret even one box, it can lead to some costly mistakes or missed deductions down the line.

The main thing to wrap your head around is that the K-1 is a "pass-through" document. The business itself—the S corp or partnership—doesn't pay the income tax. It "passes through" its profits, losses, deductions, and credits directly to you, the owner or beneficiary. It's your job to report these on your personal return, and believe me, it’s a whole lot more involved than just entering W-2 wages.

Why K-1 Reporting Requires Precision

Figuring out where each number from your K-1 goes on your 1040 is more than a simple data entry task. It's about correctly classifying the nature of your financial stake in the business, because different types of income are taxed differently.

Here’s a quick breakdown of how this plays out:

- Ordinary Business Income: This is your bread and butter, typically landing on Schedule E. If you're an active partner, this is also where self-employment tax considerations come into play.

- Interest and Dividends: These items are peeled off and moved over to Schedule B, just like the interest you'd earn from a regular savings account.

- Capital Gains: These have their own dedicated spot on Schedule D, where they're taxed at different rates than your ordinary income.

- Charitable Contributions: If the entity made donations, your share flows to Schedule A, but only if you itemize your deductions.

What this means in practice is that a single K-1 can easily touch five or more different schedules and forms that get attached to your Form 1040.

One of the biggest mistakes I see people make is assuming the cash they received from the business (their distribution) is the same as the taxable income on their K-1. These two numbers are almost never the same. You're taxed on your share of the profit, not the cash you actually took home.

When it comes to U.S. tax compliance, the IRS pays close attention to income from these pass-through entities. The rules are clear: nonpassive ordinary business income from a K-1 gets reported on Schedule E, and those totals eventually make their way to Schedule 1 of your main return.

And the IRS doesn't mess around with mistakes here. An error in how you report a K-1 can trigger penalties of up to $310 per incorrect K-1. This really underscores why getting it right is so important. For a deeper dive into this, the Tax Policy Center offers some great data on the role of pass-through businesses in the economy.

For a quick cheat sheet, I've put together a table that maps the most common K-1 boxes to their corresponding spots on your 1040. While it doesn't cover every scenario, it's a fantastic starting point for organizing your information.

Quick Reference Where K-1 Income Goes on Your 1040

| Common K-1 Box | Type of Income/Deduction | Primary Reporting Location (Form/Schedule) |

|---|---|---|

| Box 1 | Ordinary Business Income (or Loss) | Schedule E, Part II |

| Box 2 | Net Rental Real Estate Income (or Loss) | Schedule E, Part II |

| Box 5 | Interest Income | Schedule B |

| Box 6a/6b | Ordinary/Qualified Dividends | Schedule B |

| Box 8 | Net Short-Term Capital Gain (or Loss) | Schedule D |

| Box 9a | Net Long-Term Capital Gain (or Loss) | Schedule D |

| Box 13 (Code A) | Cash Contributions (Charitable) | Schedule A (if itemizing) |

| Box 13 (Code K) | Deductions – Portfolio | Schedule A (if itemizing) |

| Box 14 (Code A) | Net Earnings (or Loss) from Self-Employment | Schedule SE |

| Box 17 (Code V) | Section 199A (QBI) Information | Form 8995 or 8995-A |

| Box 20 (Code Z) | Section 199A (QBI) Dividends | Form 1040, Line 3a (Qualified Dividends) |

This table should help you quickly place the most frequent items. Always remember to cross-reference with the official K-1 instructions, as codes and reporting requirements can have unique nuances depending on the specifics of the business.

Cracking the Code: A Box-by-Box Guide to Your Schedule K-1

Getting a Schedule K-1 in the mail can be intimidating. It's not a simple W-2; it’s a detailed summary of your share of an entity's financial life for the year. The trick is to stop seeing it as one big, confusing document and instead view it as a roadmap, with each box pointing to a specific line on your personal tax return.

Think of it this way: the K-1 separates different types of income, deductions, and credits because the IRS treats them all differently. Ordinary business income isn't taxed the same way as a long-term capital gain, and certain deductions have their own unique rules. By mapping each box correctly, you ensure everything is handled properly.

Let's break down the most common boxes and trace where they land on your Form 1040 and its related schedules.

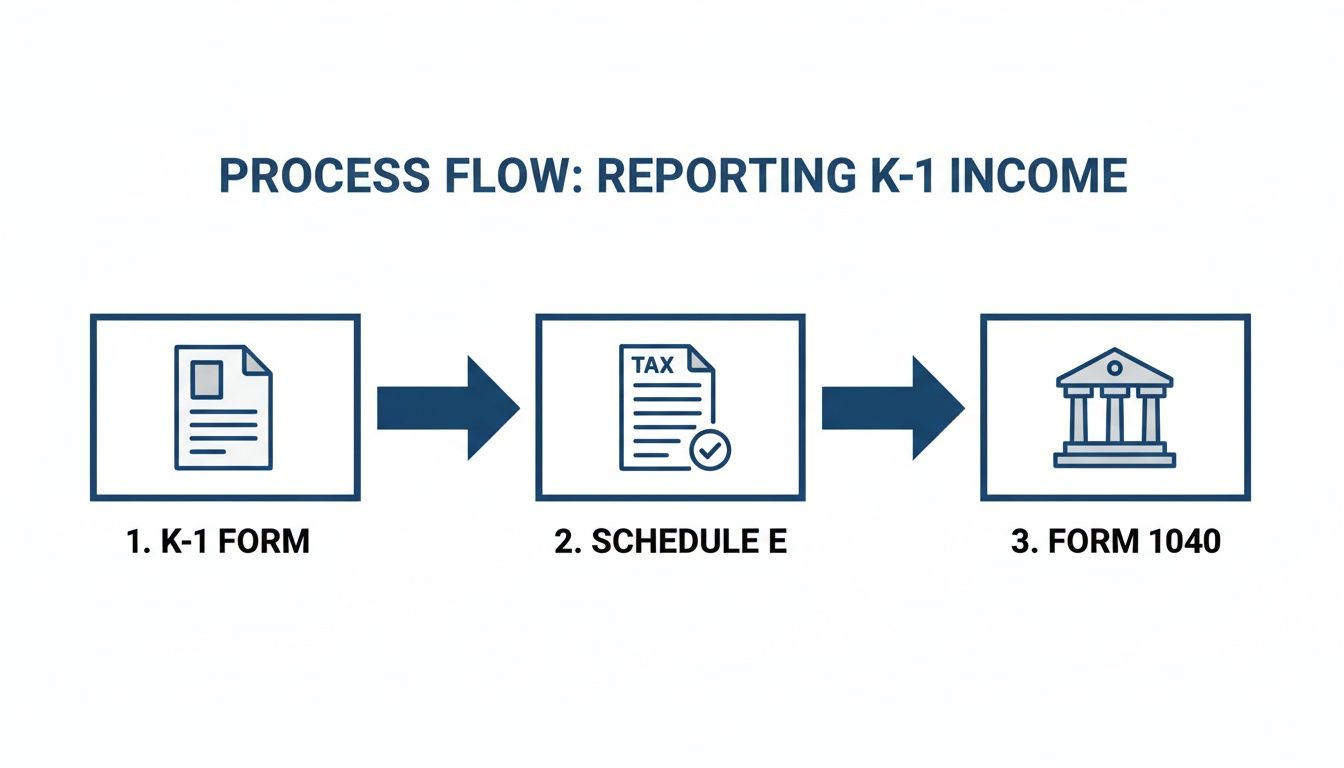

This flow chart gives you a bird's-eye view of how K-1 items typically travel from the business entity through your return.

As you can see, Schedule E acts as the central hub for most of the core business income before it all comes together on your Form 1040.

Core Income and Loss Reporting

The first few boxes are usually the heavy hitters—they represent the profit or loss from the entity's day-to-day operations and have the biggest impact on your adjusted gross income (AGI).

-

Box 1: Ordinary Business Income (or Loss): This is the bottom line from the entity's main business activity. This number goes directly onto Schedule E (Form 1040), Part II. You'll list the entity's name and EIN, then place this amount on line 28 in either the nonpassive or passive column, which depends entirely on your level of involvement in the business.

-

Box 2: Net Rental Real Estate Income (or Loss): If the partnership or S corp owns rental properties, your slice of the net income or loss shows up here. This also lands on Schedule E, Part II, but you should report it on a separate line from your Box 1 income.

-

Box 3: Other Net Rental Income (or Loss): This is for rental income from other types of property, like heavy equipment. Just like the real estate rental income from Box 2, this also gets reported on Schedule E, Part II.

It's a small but important detail: always give each K-1 its own line on Schedule E. This keeps your records clean and makes it much easier to track your basis, especially if you have investments in multiple entities.

Investment and Portfolio Income

Many businesses also have investment activities that are separate from their main operations. The K-1 breaks this income out because it's taxed differently—it's not subject to self-employment tax, for one thing.

Box 5: Interest Income

This is your share of any interest the entity earned, just like the interest you'd get from a savings account on a Form 1099-INT. This amount gets reported on Form 1040, Schedule B, Part I, line 1.

Boxes 6a and 6b: Ordinary and Qualified Dividends

Here you'll find your portion of any dividend income.

- Ordinary dividends (Box 6a) go on Schedule B, Part II, line 5.

- Qualified dividends (Box 6b) are a subset of ordinary dividends that are taxed at lower capital gains rates. You'll also note this amount when filling out line 5 of Schedule B, and it ultimately helps calculate your final tax on Form 1040, line 3a.

Boxes 8 and 9a: Net Short-Term and Long-Term Capital Gains (or Losses)

These boxes show your share of gains or losses from assets the entity sold.

- Short-term gains/losses (Box 8) flow to Schedule D, line 5.

- Long-term gains/losses (Box 9a) are reported on Schedule D, line 12.

These amounts will be combined with any personal capital gains and losses you have from your own brokerage accounts.

The crucial point here is that the K-1 intentionally separates business income (Schedule E) from portfolio income (Schedules B and D). This structure is what ensures your investment earnings aren't accidentally hit with self-employment tax and that capital gains get their favorable tax treatment.

Getting this right matters. In 2021 alone, the IRS processed 159.6 million Form 1040 returns, with a staggering 4.7 million of them including Schedule E filings directly tied to K-1s. You can explore more tax filing statistics and their implications on the BrightAdvisers website.

Deductions, Credits, and Other Items

The final part of the K-1 is a mix of other important figures that can lower your tax bill. Don't overlook these boxes.

Box 12: Section 179 Deduction

This is a powerful tax break that lets businesses write off the full cost of certain equipment right away. Your share of this deduction is reported first on Form 4562, Depreciation and Amortization, and then flows to Schedule E. Just be mindful of the annual limitations on how much you can personally deduct.

Box 13: Charitable Contributions

If the business made donations to charity, your portion will be listed here with a code (like "A" for cash). You'll carry this amount over to Form 1040, Schedule A, but only if you are itemizing your deductions.

Box 14: Self-Employment Earnings (Partnerships Only)

This box is absolutely critical for general partners and many LLC members. The amount in Box 14 (Code A) is your share of earnings that are subject to self-employment tax. You'll use this figure to fill out Schedule SE (Form 1040) and calculate what you owe for Social Security and Medicare. This box is irrelevant for S corporation shareholders.

Box 17: Qualified Business Income (QBI) Deduction Information

This box provides the raw data—your share of the business's QBI, W-2 wages, and property basis—needed to calculate the valuable Section 199A deduction. You’ll plug these numbers into Form 8995 or 8995-A. This can lead to a deduction worth up to 20% of your qualified business income, making it one of the most important boxes on the form for many business owners.

Understanding Passive vs. Nonpassive Activity

Figuring out which box to put your K-1 numbers in is just the start. The real challenge—and where many taxpayers get tripped up—is understanding why the numbers go where they do. This leads us straight into the critical distinction between passive and nonpassive activities.

This isn't just tax jargon. The classification directly controls your ability to deduct losses and can have a massive impact on your final tax bill.

The IRS created these two buckets for a specific reason: to stop people from using paper losses from a business they barely touch to wipe out their W-2 salary or other taxable income. Misclassifying your activity is one of the most frequent—and costly—mistakes I see on returns involving K-1s.

The Material Participation Test

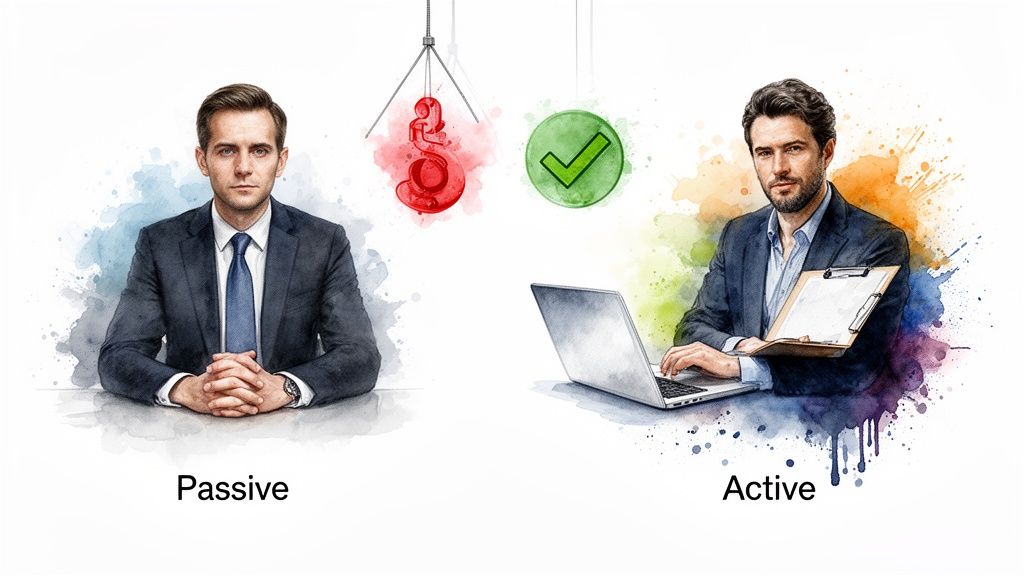

At the heart of this whole passive-versus-nonpassive debate is a single concept: material participation.

Did you work in the business on a regular, continuous, and substantial basis during the year? If the answer is yes, the income or loss is generally considered nonpassive (or "active"). If you were more of a hands-off investor, it's probably passive.

To take the guesswork out of it, the IRS has seven specific tests. You only need to meet one of these for the activity to qualify as nonpassive for the year. The most common ones we encounter are:

- The 500-Hour Test: You spent more than 500 hours working in the business during the year. This is the gold standard.

- The Substantially All Test: Your work essentially was all the work done by anyone for the activity.

- The 100-Hour Test: You put in over 100 hours, and nobody else (including non-owners) worked more than you did.

- The Significant Participation Activity (SPA) Test: This one is a bit more complex. An SPA is an activity where you spent more than 100 hours. If the total time you spent on all of your SPAs is more than 500 hours, then they all become nonpassive.

These aren't honor-system tests. They are based on facts and circumstances, which means you need to keep good records. If the IRS ever asks, you have to be able to back up your claim of material participation.

How Passive Loss Rules Can Derail Your Tax Return

So, what’s the big deal if an activity is labeled passive? If it makes money, you report the income on Schedule E and pay your tax. No problem. The real pain comes when a passive activity loses money.

Here's the rule: Passive losses can only offset passive income.

They cannot be used to lower your nonpassive income, like your salary, interest, dividends, or profits from a business you actively run.

Let's walk through a classic scenario. You're a silent partner in a friend's new restaurant, which unfortunately produced a $20,000 loss for you on your K-1. You also have a day job with a $200,000 salary. Because you're a silent partner and don't materially participate, that $20,000 loss is passive. You can't just subtract it from your salary to save on taxes.

That $20,000 loss is suspended. It gets put on the back burner, carried forward to future years, and tracked on Form 8582, Passive Activity Loss Limitations. It will sit there, unusable, until you either have passive income from another source or you sell your entire stake in the restaurant.

Don't Forget the At-Risk Limitations

Before you even get to the passive loss rules, there's another hurdle you have to clear first: the at-risk rules. This is all handled on Form 6198.

The simple version is that you can't deduct a loss that's greater than the amount you personally have "at risk" in the venture.

Your at-risk amount typically includes:

- The cash you put in.

- The tax basis of any property you contributed.

- Any loans for the business that you are personally on the hook to repay.

Imagine you invested $50,000 in a partnership. The K-1 comes back showing a $70,000 loss. Even if you were active in the business, you can only deduct $50,000 of that loss this year. The other $20,000 is suspended until you increase your at-risk amount, perhaps by contributing more capital. This is another key reason why professional guidance is so valuable—navigating these layered limitations is crucial for staying compliant.

Navigating Self-Employment Tax and QBI Deductions

Once you've mapped the basic income and loss items from a K-1 to your return, the real work often begins. Two of the biggest moving parts are the self-employment tax and the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction. How you handle these can swing your tax liability by thousands of dollars, so it pays to get them right.

These aren't just obscure lines on a form; they represent fundamental differences in how the IRS treats various business structures. A simple misunderstanding can lead to a nasty surprise at tax time or, just as bad, leaving valuable deductions on the table.

The Impact of Self-Employment Tax

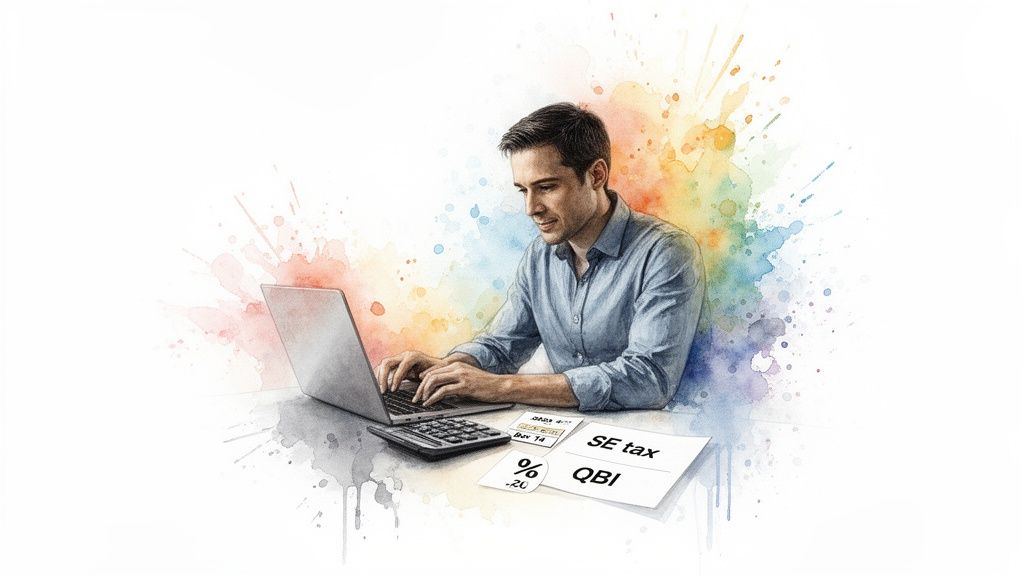

If you're a partner in a partnership or a member of an LLC, Box 14 (Code A) on your K-1 is a number you cannot ignore. This figure represents your "Net earnings (loss) from self-employment" and is your starting point for calculating Social Security and Medicare taxes.

This income flows directly over to Schedule SE, Self-Employment Tax. It's critical to remember this is a completely separate tax from your income tax. Think of it as the price of doing business for yourself—a direct tax on your earnings from being actively involved in the trade or business.

One of the most common tripwires I see involves the distinction between general and limited partners. Generally, a general partner’s share of the business income is subject to self-employment tax. A limited partner, who by definition isn't active in the business, usually isn't. The lines get fuzzy with LLCs, where "managing members" are often treated like general partners for tax purposes, making their earnings subject to SE tax.

This is precisely where the S corporation structure can be so attractive from a tax planning standpoint. Unlike partners, S corp shareholders don't pay self-employment tax on their profit distributions. Instead, they must take a "reasonable salary," which is subject to standard payroll taxes. This split is one of the main reasons many business owners make the S corp election.

Maximizing the Qualified Business Income Deduction

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 handed a major tax break to owners of pass-through businesses: the Qualified Business Income (QBI) deduction. Also known as the Section 199A deduction, this powerful provision allows eligible taxpayers to deduct up to 20% of their qualified business income.

Your K-1 is the key that unlocks this deduction. The specific data you need is located in different boxes depending on the entity, but it’s typically found in Box 17 for S corporations or Box 20 for partnerships.

These boxes will provide a breakdown of your share of the business's:

- Qualified Business Income (QBI): The net profit from the business operations.

- W-2 Wages: Your portion of the wages the business paid to all its employees.

- UBIA of Qualified Property: The "unadjusted basis immediately after acquisition" of business property.

With this information in hand, you’ll complete either Form 8995, Qualified Business Income Deduction Simplified Computation, or its more complex sibling, Form 8995-A. The form you use depends on your taxable income before the QBI deduction. For 2023, the key thresholds were $182,100 for single filers and $364,200 for married couples filing jointly.

If your income falls below those thresholds, the calculation is usually straightforward—your deduction is simply 20% of your QBI. But if your income is higher, things get more complicated. The deduction can be limited by either 50% of your share of W-2 wages or a combination of 25% of wages plus 2.5% of the property basis (UBIA).

The type of business you're in also becomes critical at higher income levels. If you own a "Specified Service Trade or Business" (SSTB)—think doctors, lawyers, accountants, or consultants—the QBI deduction begins to phase out and can disappear entirely once you cross the income thresholds.

Partnership vs S Corp K-1 Income Treatment

The choice between operating as a partnership or an S corporation has significant tax implications that show up directly on your K-1. Here’s a quick comparison of how some key items are handled.

| Tax Item | Partnership (Form 1065 K-1) | S Corporation (Form 1120-S K-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-Employment Tax | Ordinary business income (Box 1) is generally subject to SE tax for active partners (this amount is reported in Box 14). | Profit distributions are not subject to SE tax. However, shareholder-employees must take a reasonable salary, which is subject to FICA and other payroll taxes. |

| Health Insurance | Premiums paid for a partner are treated as guaranteed payments. They're deductible by the partnership and reported as income to the partner, who can then deduct them on Form 1040. | Premiums for a >2% shareholder are included in their W-2 wages. The shareholder can then take an above-the-line deduction for the premiums on Schedule 1 of their 1040. |

| Basis Calculation | A partner's basis in the partnership includes their share of the entity's debt, which can allow for larger loss deductions. | A shareholder's basis does not include any of the S corporation's debt, which can limit the ability to deduct losses. |

Understanding these differences is about more than just filling out a tax return correctly; it's about making smart, strategic decisions for your business. The entity structure you choose creates ripples that affect your personal tax situation for years to come. If you're navigating these choices, getting advice from a professional at Blue Sage Tax & Accounting Inc. can help ensure your business structure is truly working for you.

Beyond the Basics: Common K-1 Mistakes and Complex Scenarios

Once you've mastered mapping the basic K-1 boxes to your Form 1040, you’ve reached the edge of the map. This is where real-world complexity begins, and simple data entry gives way to a more nuanced, strategic approach to your taxes.

Even seasoned investors can get tripped up by these advanced scenarios. Getting them wrong can lead to costly errors, missed deductions, or the kind of letter from the IRS that no one wants to receive. Let's dig into the tricky situations that require you to look beyond the numbers on the page and consider your entire financial picture.

The All-Important Job of Tracking Your Basis

If there’s one responsibility S corporation shareholders and partners frequently overlook, it’s tracking their basis. Think of your basis as your total economic stake in the business. It’s not a static number—it goes up when you contribute capital or get your share of profits, and it goes down when you take distributions or absorb losses.

So, why does this matter so much? Because your basis is the ultimate gatekeeper for your deductions. You simply can't deduct losses that exceed your basis.

Let's say your K-1 shows a $30,000 business loss, but your basis in the S corporation is only $10,000. You can only write off $10,000 of that loss on this year's return. The other $20,000 gets suspended and carried forward. You can use it in a future year, but only once you have enough basis to cover it—either by putting more money into the business or when it starts turning a profit again. Remember, the business isn't required to track this for you; the buck stops with you.

A classic mistake is to assume the capital account listed on your K-1 is the same as your basis. They're related, but not identical, especially in a partnership where your basis also includes your share of the entity's debt. Failing to track this accurately is a recipe for either overstating your losses or miscalculating the gain when you eventually sell your stake.

Juggling Multi-State Investments

When a partnership or S corp does business across state lines, your tax return gets a lot more interesting. Your K-1 will usually come with a supplemental schedule that breaks down your share of income for each state the business operated in.

This almost always means you'll have to file nonresident state income tax returns in every state that sourced you income. This is a common "gotcha" for investors who live in one state but are unknowingly earning money in several others through their K-1 investment.

The silver lining here is the credit for taxes paid to other states. For instance, if you end up paying $2,500 in income tax to California on your K-1 earnings, you can typically claim a credit for that amount on your home state's return (let's say it's New York) to avoid being taxed twice on the same income. This takes careful coordination and filing the proper state credit forms, but it's crucial for avoiding overpayment.

When a Late or Amended K-1 Shows Up

It’s a scenario that plays out every tax season: you’ve already filed your return, feeling relieved, and then another envelope arrives. It’s a corrected or late Schedule K-1.

What do you do? Ignoring it is not an option. The IRS gets the same copy, and its automated systems are designed to spot discrepancies between what the business reported and what you did. A mismatch is a surefire way to trigger a notice.

The proper way to handle this is to file an amended return using Form 1040-X, Amended U.S. Individual Income Tax Return. You'll use it to report the new numbers, explain the change, and recalculate your tax. You’ll either owe a bit more or, hopefully, get a refund. It's an administrative hassle, no doubt, but it's far less painful than dealing with penalties and interest down the road.

Navigating International Tax Considerations

If your K-1 comes from a foreign partnership or a U.S. entity with foreign operations, you’re stepping into an entirely different level of tax reporting. The K-1 might report items like foreign taxes paid on your behalf or income sourced from another country, each with its own set of rules.

Here are a few key things to be on the lookout for:

- Foreign Tax Credit: If the business paid foreign taxes on your share of the income, you might be able to claim a credit against your U.S. tax bill using Form 1116. This prevents double taxation and is a critical benefit to claim.

- Extra Reporting: Your investment could trigger additional filing requirements. For example, you may need to report your interest as a specified foreign financial asset on Form 8938.

These international rules are notoriously complex and tangled up in tax treaties and specific U.S. laws. This is one area where getting professional advice isn't just a good idea—it's often a necessity.

Common Questions About K-1 Income

Even the most seasoned investors run into tricky situations with Schedule K-1s. Let's tackle some of the most common questions that pop up every tax season.

I Haven't Received My K-1 and the Deadline is Looming. What Now?

This is an incredibly common—and frustrating—scenario. The absolute best thing you can do if your K-1 hasn't shown up by the April tax deadline is to file for an extension using Form 4868. This automatically gives you another six months to get your return filed correctly.

Whatever you do, resist the urge to file your return using estimated numbers. You'll almost certainly have to file an amended return later, which is a much bigger headache. An extension gives the business more time and gives you a chance to check in with the partnership or S corp for an updated timeline.

If the extended deadline is approaching and you're still empty-handed, you can file Form 8082, Notice to IRS of Inconsistent Treatment. This form is your way of telling the IRS you're reporting information differently than what the (missing) K-1 would show, and it lets you explain why.

Can I Use My K-1 Losses to Lower the Tax on My W-2 Salary?

It's the million-dollar question for many investors, but the answer is almost always no. Trying to deduct a business loss against your regular W-2 income is tough because of several major tax hurdles. Before you can even consider it, the loss has to clear your tax basis and at-risk limitations.

The biggest roadblock, however, is usually the passive activity loss rules. If you don't "materially participate" in the day-to-day operations of the business, its losses are considered passive. And passive losses can only be used to offset passive income—not "active" income like your salary.

Any losses you can't use are suspended and carried forward. You can use them to offset passive income in future years, or you can typically deduct them in full when you eventually sell your entire stake in the business.

Why Is My K-1 Income Different From the Cash I Received?

This is probably the single biggest point of confusion for new K-1 recipients. It all comes down to a simple fact: taxable income and cash distributions are two completely different things. You are taxed on your share of the business's net income, whether or not that money ever lands in your bank account.

For instance, a partnership might earn $100,000 in profit but decide to reinvest that money to buy new equipment instead of paying it out. You'll still get a K-1 showing your share of that $100,000 in taxable income, and you'll owe tax on it—even if you didn't receive a dime.

On the flip side, you could receive a cash distribution that's larger than your share of the income. This might be a non-taxable return of your original investment (known as a return of capital). In that case, it wouldn't be taxed as income but would instead simply reduce your investment basis in the company.

Navigating the complexities of K-1s, from multi-state filings to basis tracking, requires careful planning. At Blue Sage Tax & Accounting Inc., we partner with investors and business owners to provide proactive tax strategies that align with your financial goals. Learn how our expertise can bring clarity to your tax situation.