The U.S.-India tax treaty is essentially a pact to solve a thorny problem: how to stop individuals and companies from getting taxed twice on the same dollar (or rupee) of income. It's a financial rulebook that decides whether the U.S. or India gets the first—or only—bite at taxing your salary, business profits, or investment gains when you have a connection to both countries.

The real goal here is to grease the wheels for trade and investment between the two nations by making the tax consequences clear and predictable.

A Financial Bridge Between Two Nations

Trying to navigate the tax systems of both the United States and India at the same time can be maddening. It often feels like you’re playing a game where two different referees are on the field, each with their own rulebook. This confusion can easily lead to double taxation, where you're paying tax on the same income in both countries.

The U.S.-India tax treaty cuts through that complexity. It acts as the essential bridge connecting two very different tax regimes, creating a single, predictable path for people and businesses operating across borders.

This agreement isn't just a dry legal document; it's a cornerstone of the economic partnership between two of the world's major democracies. It’s all about making sure that income flowing between the two countries gets taxed fairly—and just once.

What the Treaty Aims to Accomplish

At its core, the treaty is designed to do a few critical things for anyone with financial ties to both the U.S. and India.

Eliminate Double Taxation: This is the big one. The treaty sets out which country gets to tax what. It designates taxing rights to either the "source country" (where the money is made) or the "residence country" (where the taxpayer lives), so you aren't hit with the full tax bill from both sides.

Create Tax Certainty: By laying out clear, consistent rules for everything from dividends to pensions, the treaty gives you a reliable map to follow. This makes financial planning and business forecasting much less of a guessing game.

Lower Withholding Taxes: For certain types of income—think dividends, interest, and royalties—the treaty often slashes the withholding tax rates that would normally apply. This leaves more money in the hands of the taxpayer.

Combat Tax Evasion: The treaty isn't just about providing relief. It also includes provisions for the IRS and Indian tax authorities to share information, helping them work together to catch those trying to dodge their tax obligations.

The formal agreement, signed on September 12, 1989, was a landmark in U.S.-India relations. As the first comprehensive tax treaty between the two countries, it was uniquely structured to acknowledge India's position as a developing nation at the time. This led to certain provisions that you won't find in typical U.S. tax conventions. You can review the full treaty history as documented by the U.S. Congress to see how it came together.

Figuring Out Your Tax Residency Status

Before you can even think about using the U.S.–India tax treaty, you have to answer one critical question: for tax purposes, where do you officially live? Article 4 of the treaty is the rulebook for this, and it’s not as simple as counting the days you spend in each country. The goal is to establish a single, definitive country of residence, even if your life and business straddle both nations.

Each country has its own way of defining a tax resident. In the U.S., it often boils down to the Substantial Presence Test—a straightforward day-counting formula. India has its own similar rules based on physical presence. The real headache starts when you meet the domestic residency rules for both countries in the same year.

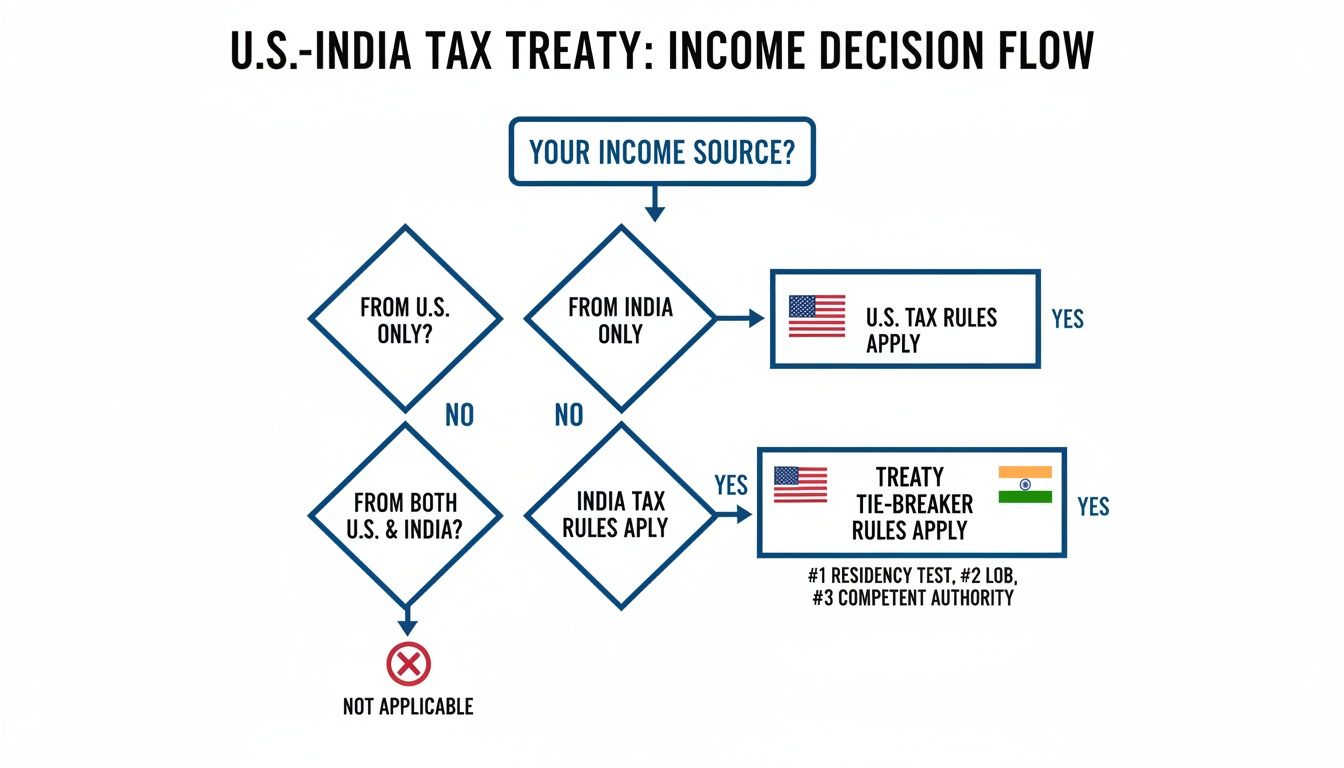

This is where you're considered a "dual resident," and it's precisely the problem the treaty's tie-breaker rules were designed to solve. The flowchart below gives you a quick visual of how the treaty steps in to decide which country gets taxing rights based on where your income comes from.

As you can see, when your financial life is split between both countries, the treaty is the essential guide for sorting things out.

How the Tie-Breaker Rules Work

When both the U.S. and India claim you as a tax resident, Article 4 lays out a clear, step-by-step process to break the tie. Think of it as a series of cascading questions. You have to answer them in order, and the first one that gives a clear answer determines your residency for the treaty.

You can't skip ahead or pick the test you like best. Here’s the sequence:

Permanent Home Available: The first question is, where do you have a permanent home? This isn't just a place you visit; it's a dwelling you own or rent that's continuously available to you. If you only have a permanent home in one of the two countries, the analysis stops there. That's your tax home.

Center of Vital Interests: What if you have a home in both countries (or in neither)? The next step is to figure out where your personal and economic ties are stronger. This is a bit more subjective, weighing things like where your family is, your social life, your primary business activities, and where you manage your assets. The country where these "vital interests" are clustered becomes your tax residence.

Habitual Abode: If your vital interests are split pretty evenly and it's too close to call, the tie-breaker looks at your "habitual abode"—a fancy way of asking where you physically spend more time. Tax authorities will analyze your travel patterns over a reasonable period to see where you more frequently live.

Citizenship: If you’ve gone through all three tests and the answer is still ambiguous (which is rare), your citizenship is the final decider. If you're a citizen of only one of the two countries, you'll be treated as a resident of that country.

A Real-World Example

Let's put this into practice. Imagine Anjali, an Indian citizen and tech executive. She owns an apartment in Bangalore where her family lives, but she's also renting a condo in Silicon Valley for a long-term project and spends a lot of time there.

- Permanent Home: Anjali has a permanent home available in both India and the U.S., so this test doesn't resolve her status.

- Center of Vital Interests: This is tricky. Her family and social connections are in India, but her primary income and career focus are currently in the U.S. It could be argued either way.

- Habitual Abode: If she spends, say, 200 days a year in the U.S. and 165 days in India, her habitual abode would point to the U.S.

- Citizenship: If, for some reason, the habitual abode test was also inconclusive, her Indian citizenship would be the deciding factor, making her a resident of India for treaty purposes.

It's crucial to remember that the tie-breaker rules are a mandatory sequence, not a menu of options. You must follow the steps in order. The entire process is designed to find one, and only one, tax home so that the U.S.–India treaty can be applied correctly.

Key Treaty Provisions for Businesses and Investors

For anyone with cross-border business or investment activities, the U.S.-India tax treaty is far more than a dry legal document. It's a practical financial tool that directly impacts your bottom line. At its core, the treaty lays out a clear set of rules that define which country gets to tax certain income, often reducing the tax bite on profits, dividends, and other payments.

Getting a handle on these key articles is the first step toward smart international tax planning.

The Permanent Establishment Footprint

The most fundamental question for any business operating abroad is simple: Where do we pay tax on our profits? Article 5 of the treaty answers this with the concept of a Permanent Establishment, or PE.

Think of a PE as a "business footprint." If your company's presence in the other country is significant enough to leave a lasting footprint, that country earns the right to tax the profits you generate there. This is a crucial anti-avoidance rule that stops companies from earning substantial revenue in a foreign market without contributing to its tax base.

A PE isn't just about renting an office. The treaty defines it broadly as any fixed place of business. This can include:

- A branch office or place of management

- A factory, workshop, or warehouse

- A mine, an oil or gas well, or any other site for extracting natural resources

- A construction or building project that lasts for more than 120 days

The takeaway is straightforward: If a U.S. company creates a PE in India, its profits attributable to that Indian operation can be taxed by India. Without a PE, those business profits are generally only taxable back home in the U.S.

Reducing Taxes on Passive Investment Income

Beyond active business profits, the treaty provides major relief for investors earning passive income like dividends, interest, and royalties. It does this by capping the withholding tax rates that the source country can apply. A withholding tax is exactly what it sounds like—a tax collected "at the source" before the payment ever leaves the country.

Without the treaty's protection, domestic tax laws in both countries would impose much higher rates, taking a significant chunk out of investment returns. The specific caps laid out in the U.S.-India treaty are a cornerstone of cross-border investment, providing predictability and lowering the overall tax burden. For those who want to dive into the specifics, the official text of the convention is available from the IRS.

The table below gives a quick overview of just how much of a difference the treaty makes.

U.S.-India Tax Treaty Withholding Rates At A Glance

The following table compares the standard domestic withholding tax rates in both countries with the reduced rates available under the U.S.-India tax treaty for key income types.

| Income Type | Standard Domestic Rate (Typical) | Treaty Rate | Key Conditions/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dividends | 20-30% | 15% or 25% | The 15% rate applies if the beneficial owner is a company holding at least 10% of the voting stock of the payer. Otherwise, the rate is 25%. |

| Interest | 20-30% | 10% or 15% | A 10% rate applies to interest from loans by banks and similar financial institutions. A 15% rate applies in most other cases. Some government interest is exempt. |

| Royalties & Fees for Included Services (FTS) | 20-30% | 10% or 15% | This unique provision covers payments for technical or consultancy services. The rate is 10% for royalties/FTS from equipment rentals and 15% for others. |

As you can see, these reductions are significant. They are one of the most tangible benefits of the treaty, ensuring that investors, inventors, and service providers can keep more of their hard-earned cross-border income.

Navigating Capital Gains Taxation

Finally, Article 13 of the treaty deals with the tax on capital gains—the profit you make from selling an asset like real estate, stocks, or a piece of a business. The rules here are quite nuanced, and the right to tax a gain depends entirely on what kind of asset was sold.

Key Insight: The guiding principle for capital gains is that the country where the asset is physically located usually has the primary right to tax the gain. This is especially true for real estate.

Here’s a simplified breakdown of how it works:

Immovable Property (Real Estate): Gains from selling real estate are taxed where the property sits. Sell a building in Mumbai, and India has the right to tax that gain, no matter where you live.

Movable Property of a Permanent Establishment: If a business sells assets (like machinery) that are part of its PE in the other country, the gain is taxed in the country where the PE is located.

Shares of Stock: This is where it gets more complicated. As a general rule, gains from selling shares of a company are taxable only in the seller's country of residence. However, there's a big exception: if the company's value comes principally from real estate in the other country, that other country may also get to tax the gain.

These provisions for business and investment are the heart of the U.S.-India tax treaty. They provide a clear roadmap for reducing tax friction and encouraging the flow of capital and commerce between the two economic giants.

A Practical Guide to Claiming Treaty Benefits

Knowing the U.S.-India tax treaty exists is one thing. Actually putting its benefits into your pocket is another matter entirely. The whole process hinges on specific, timely paperwork that proves your eligibility to the tax authorities.

Get this part wrong, and you could end up overpaying tax through excessive withholding or, worse, getting hit with double taxation. This section is your roadmap to navigating the compliance side of things. The key is to be proactive—get the right forms in the right hands before payments are made and when you file your returns.

Securing Reduced Withholding with Form W-8BEN

If you're an individual living in India and earning certain types of U.S.-source income, your most important tool is Form W-8BEN, Certificate of Foreign Status of Beneficial Owner for United States Tax Withholding and Reporting (Individuals). This isn't a form you file with the IRS. Instead, you give it directly to the U.S. withholding agent—the company or person paying you.

Think of Form W-8BEN as your official heads-up. You're essentially telling the U.S. payer, "I'm a resident of India, and under our tax treaty, you should only withhold at the lower treaty rate, not the default 30%."

For businesses and other entities based in India, the equivalent is Form W-8BEN-E. It serves the same function but is far more detailed, asking for information about the company's structure to prevent "treaty shopping" abuses.

Eliminating Double Taxation with Foreign Tax Credits

Getting a lower withholding rate is just the first step. What if you've already paid tax in India on income that the U.S. also wants to tax? This is where the foreign tax credit (FTC) becomes your best friend. It’s the treaty's core mechanism for making sure the same income isn't taxed twice.

The FTC lets you reduce your U.S. income tax bill, dollar-for-dollar, for the income taxes you've already paid to the Indian government. It's the U.S. tax system's way of giving you credit for taxes paid abroad.

To claim it, you’ll need to file a specific form with your U.S. tax return:

- Individuals and Estates: File Form 1116, Foreign Tax Credit, to calculate the exact credit you can claim against your U.S. tax liability.

- Corporations: The corporate equivalent is Form 1118, Foreign Tax Credit—Corporations.

Putting it all together: Imagine an Indian resident receives $10,000 in dividends from a U.S. company. By submitting a valid Form W-8BEN, they ensure the U.S. payer withholds at the 25% treaty rate ($2,500) instead of the standard 30%. Later, when filing their Indian tax return, they can claim a credit for the $2,500 in U.S. taxes paid, preventing that income from being fully taxed all over again.

When you master these steps, the U.S.-India tax treaty transforms from a dense legal document into a powerful tool for tax efficiency. Proactive paperwork and accurate FTC claims are what make the difference between theory and real-world savings.

Moving Beyond the Basics: Advanced Provisions and Dispute Resolution

Once you've grasped the fundamentals of residency, P.E., and withholding rates, it's time to look at the finer print. The U.S.-India tax treaty isn't just about setting rates; it also includes critical mechanisms for handling the messy, real-world complexities of cross-border business and investment. These advanced articles are the treaty's problem-solvers and guardrails, designed to resolve disputes and prevent abuse.

For high-net-worth individuals and multinational businesses, these provisions are where the real strategic thinking comes into play. Two of the most significant are the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP), which provides a path to resolve conflicts, and the Limitation on Benefits (LOB) article, which ensures the treaty is used for its intended purpose.

Getting Help When Things Go Wrong: The Mutual Agreement Procedure

So what happens when you’ve done everything by the book, but you still get hit with a tax bill that feels like double taxation? This is precisely why Article 27, the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP), exists. It’s a formal, government-to-government channel for taxpayers who believe their tax treatment goes against what the treaty promises.

Think of MAP as your diplomatic lifeline. When you initiate a MAP case, you’re essentially asking the "competent authorities" of both countries—the IRS for the U.S. and the Central Board of Direct Taxes for India—to sit down and hash out a solution on your behalf. It’s not for simple matters; it’s for thorny issues like transfer pricing disagreements or conflicting interpretations of whether a permanent establishment exists.

Engaging in the MAP process is a significant step, but it’s an indispensable tool for ensuring the core goal of the treaty—avoiding double taxation—is actually met in practice, especially in high-stakes, contentious scenarios.

Closing the Loopholes: Preventing "Treaty Shopping"

The favorable terms of the treaty, like lower withholding tax rates, are meant for genuine residents of the U.S. and India. Not for outsiders looking for a backdoor to tax savings. To guard against this, the treaty contains a powerful anti-abuse provision called the Limitation on Benefits (LOB) article.

The LOB article is all about preventing "treaty shopping." This is when a resident of a third country—say, a European company—sets up a shell entity in India purely to take advantage of the U.S.-India treaty's benefits for its U.S. investments. The LOB provision establishes a series of objective tests to prove a person or company has a legitimate, substantial connection to their country of residence.

Key Takeaway: The LOB article is the treaty's gatekeeper. To get the benefits, you have to be a "qualified person." This usually means you're a publicly traded company, an individual, or a private company that meets strict ownership and "base erosion" tests. If you can't pass the tests, you can be denied treaty benefits entirely.

This rule emphasizes that in international tax, substance always trumps form. It reflects a mutual commitment by both countries to foster genuine bilateral trade, a relationship that saw commerce in goods and services balloon from about $45 billion in 2006 to over $70 billion just a few years later in 2010. You can explore more details on this growing economic relationship.

How the Treaty Fits into the Bigger Picture

Finally, remember that the treaty doesn't exist in a vacuum. It has to coexist with a whole ecosystem of other tax laws. Here’s what you absolutely need to know:

- FATCA Compliance: The treaty runs parallel to U.S. disclosure laws like the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA). FATCA's requirements for foreign banks to report on their U.S. account holders are completely separate, and the treaty provides no exemption from them.

- State and Local Taxes: This is a crucial distinction. The U.S.-India tax treaty is a federal agreement. It has no bearing on state or local taxes. An Indian company with a permanent establishment in California, for example, is still fully on the hook for California's franchise tax.

Common Questions on the U.S.-India Tax Treaty

Even when you have a good grasp of the rules, applying the U.S.-India tax treaty to real-life situations can get tricky. The specifics of visa statuses, state tax laws, and different income streams often create confusion. Let’s tackle some of the most common questions we hear, moving beyond theory to give you practical answers.

The goal here is to provide clear, actionable guidance for the scenarios you're most likely to face.

I’m an Indian Citizen on an H-1B Visa in the U.S. How Does the Treaty Affect Me?

This is a classic situation. If you’re in the U.S. on an H-1B, you'll almost certainly meet the Substantial Presence Test, which makes you a U.S. resident for tax purposes. At that point, your focus shifts from using the treaty to avoid U.S. tax to using it to prevent double taxation on any income you still earn back in India.

You’re now required to report your worldwide income on your U.S. tax return. That includes things like rent from a property in Mumbai, interest from an Indian bank account, or capital gains from Indian investments.

This is where the treaty becomes incredibly helpful. Under Article 25, you can claim a foreign tax credit for the income taxes you've already paid to India on that specific income. You’ll use Form 1116 to do this, and it directly reduces your U.S. tax bill, ensuring you don't get hit twice for the same earnings.

Does the U.S.-India Tax Treaty Apply to State Taxes?

No, it doesn't. This is a critical point that trips up a lot of people. The tax treaty is a federal-level agreement between the two national governments. It only covers U.S. federal income taxes and specific Indian taxes, like their income tax.

The treaty offers absolutely no relief from state or local taxes. This has major implications for both people and companies.

- For Individuals: If you live and work in a state with its own income tax, like California or New York, you are on the hook for those taxes. The treaty won't lower that bill.

- For Businesses: An Indian company with a "permanent establishment" in a U.S. state will owe state corporate or franchise taxes, completely separate from any federal obligations covered by the treaty.

Crucial Takeaway: Always plan for state and local taxes separately. Don't assume treaty benefits will trickle down to your state tax return—they won’t.

My U.S. Company Hired an Indian Consulting Firm. Do We Withhold Tax?

This is one of the most complex areas of the treaty, and the answer comes down to the exact nature of the services. You need to figure out if you're paying for "included services" under Article 12 or standard "business profits" under Article 7.

It's considered "Fees for Included Services" (FIS) if the consulting work is technical or managerial and essentially "makes available" knowledge or skills to your team. Think of it this way: are they teaching your people how to do something themselves? If so, you're generally required to withhold U.S. tax, usually at the reduced treaty rate of 15%.

On the other hand, if it’s just routine professional advice that doesn’t transfer any proprietary know-how, it’s likely considered business profits. As long as the Indian firm has no permanent establishment in the U.S., you don't have to withhold any tax. Getting this wrong can lead to steep withholding liabilities and penalties, so it pays to be careful.

How Are Pensions and U.S. Social Security Handled?

The treaty treats these two types of payments very differently.

Under Article 20 (Private Pensions and Annuities), a private pension is generally taxed only where the recipient lives. For example, if a resident of India gets a pension from a former U.S. employer, only India gets to tax that income. The U.S. can't touch it.

U.S. Social Security is the big exception. Article 20, Paragraph 3 carves out a special rule giving the source country—the U.S.—the right to tax these benefits. This means the U.S. can and does tax Social Security payments, even when they're sent to a resident of India. India can also tax the income (based on residency), but to avoid double taxation, the recipient can claim a foreign tax credit in India for the U.S. taxes they paid. This dual taxing right makes Social Security a unique animal under the treaty.

Navigating the complexities of the U.S.-India tax treaty requires expert guidance to ensure compliance and optimize your financial position. At Blue Sage Tax & Accounting Inc., we specialize in international tax matters for individuals and businesses. Schedule a consultation with our team today to develop a proactive strategy that aligns with your cross-border goals.