Private equity fund accounting is the specialized financial reporting framework that governs the entire lifecycle of a private equity fund. It’s a world away from standard corporate bookkeeping. This discipline is built to handle the unique, complex relationships between fund managers and their investors, managing everything from capital commitments and asset valuations to intricate profit-sharing agreements.

At its core, this accounting practice provides the financial transparency and structural integrity a fund needs to operate effectively over its 10-to-12-year lifespan.

What is Private Equity Fund Accounting?

Imagine a private equity fund as a long-term, high-stakes construction project. A group of investors (the Limited Partners, or LPs) commit capital to an expert developer (the General Partner, or GP). The GP then uses that capital to acquire land, manage construction, and eventually sell the finished building for a profit.

Private equity fund accounting is the master blueprint and financial ledger for that entire venture.

It goes far beyond just tracking cash flow. This specialized accounting system meticulously manages the complex financial agreement between the GP and every LP. It’s responsible for answering the most critical questions:

- How much capital has each investor contributed to date?

- What is the current, fair-market value of the fund's portfolio companies?

- When a company is sold, how are the profits split among everyone involved?

The Key Players and Their Stakes

To really get a handle on fund accounting, you first have to understand the people at the table and what they need from the numbers.

General Partners (GPs): These are the fund managers. They’re the ones sourcing deals, managing the portfolio companies, and executing the fund's strategy. From an accounting standpoint, their world revolves around calculating management fees and their share of the profits—the carried interest.

Limited Partners (LPs): These are the investors who supply the fund's capital. LPs are often large institutions like pension funds, university endowments, family offices, or high-net-worth individuals. They have no say in the day-to-day operations and rely entirely on the fund's accounting reports for a clear picture of their investment's performance.

Why Standard Accounting Just Doesn't Work

So, why can't a fund just use QuickBooks? The simple answer is that private equity is a completely different beast. It operates on long timelines with illiquid assets and is governed by highly customized partnership agreements that dictate every dollar's movement.

Private equity funds are closed-end vehicles, meaning LPs commit capital for a fixed term, often 10 years or more. This long-term, locked-up structure requires a bespoke accounting framework that can manage irregular capital calls, complex profit-sharing models (waterfalls), and periodic, subjective asset valuations.

Unlike a public company with a stock price that updates every second, the private companies in a fund's portfolio must be valued manually at set intervals. This valuation process is a cornerstone of fund accounting, as it directly determines the fund’s Net Asset Value (NAV)—the single most important metric for LPs.

This unique environment of capital calls, distributions, and complex fee structures demands a robust and tailored accounting system. It’s the only way to maintain trust and provide clarity between GPs and LPs over the decade-plus life of their partnership.

Core Components of Private Equity Fund Accounting

To bring this all together, here is a breakdown of the essential pillars that make up private equity fund accounting. Each component serves a distinct purpose in tracking the fund's health and ensuring all partners receive their fair share.

| Component | Primary Purpose | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Capital Accounts | Tracks each LP's individual financial stake and activity in the fund. | Partner's Capital Balance |

| Capital Calls | The process of requesting committed capital from LPs to fund investments. | Unfunded Commitment |

| Distributions | Returning cash to LPs after an investment is successfully exited. | DPI (Distributions to Paid-In Capital) |

| Valuation & NAV | Periodically assessing the fair market value of illiquid portfolio assets. | Net Asset Value (NAV) |

| Fee Calculations | Calculating management fees and performance fees (carried interest). | Hurdle Rate & Preferred Return |

| Waterfall Model | The tiered structure that dictates the order and amount of profit distribution. | IRR (Internal Rate of Return) |

These components work in concert to create a complete and accurate financial picture, forming the bedrock of a fund's operational integrity.

How Capital Contributions and Distributions Work

At its heart, a private equity fund is all about the carefully managed flow of cash. Money moves from the investors, known as Limited Partners (LPs), to the fund manager, the General Partner (GP), and then hopefully, back to the LPs with a healthy profit. These two key movements—contributions and distributions—are the bookends of the investment lifecycle, all governed by the fund's legal agreements.

Unlike buying a public stock where you pay the full amount upfront, private equity runs on a commitment model. LPs pledge a certain amount of capital but don’t hand it all over at once. Instead, they provide the funds as the GP finds promising investment opportunities. This “just-in-time” approach is far more efficient, ensuring cash isn’t just sitting around earning nothing.

The Capital Call Process Explained

When the GP zeros in on a company to acquire, they initiate a capital call. This is the formal request asking LPs to send in a portion of their total commitment. It’s the mechanism that turns a promise of funding into actual dollars ready to be invested.

Think of it like building a custom home. You agree on the total price with your contractor upfront, but you don't pay it all on day one. You pay in stages—when the foundation is poured, when the framing is up, and so on. The GP is the contractor, calling on the LPs for funds only when they’re needed for the next phase of the "project."

This is where meticulous private equity fund accounting becomes absolutely critical. The fund accountant has to track every LP’s total commitment, how much has been called to date, and the remaining unfunded commitment.

A Practical Capital Call Example

Let's put this into a real-world scenario. Imagine a real estate fund with $100 million in total commitments from all its LPs. The GP decides to buy a commercial property for $10 million. To fund the deal, the GP issues a capital call for 10% of each LP's total commitment.

Here’s how that plays out for a single LP who committed $5 million to the fund:

- Call Notice: The LP gets a formal notice requesting their 10% share, which comes out to $500,000.

- Funds Transfer: The LP wires that $500,000 to the fund's designated bank account.

- Accounting Entry: The fund’s accountant records the cash. On the books, that LP's "paid-in capital" increases by $500,000, and their remaining "unfunded commitment" drops to $4.5 million.

This cycle repeats every time the GP makes a new investment, until all the capital is called or the fund's investment period expires.

Understanding Fund Distributions

Fast forward a few years. The fund starts selling off its investments, hopefully for a significant gain. When a portfolio company is sold, the cash proceeds are returned to the LPs through a distribution. This is the moment every investor has been waiting for—when they start seeing a return on their capital.

These payouts aren't random; they're highly structured. The first priority is usually to return the LPs' original invested capital. After that, profits are split according to the fund's waterfall model.

A crucial concept in fund accounting is the difference between a Return of Capital (getting your initial investment back) and a Return on Capital (the profits you earned). Proper reporting must clearly distinguish between the two, as it has major implications for tax and performance measurement.

The ultimate measure of success is whether this entire cycle generates strong returns. For example, the massive California Public Employees' Retirement System (CalPERS) reported its Private Equity Program achieved a net multiple of 1.5x on invested capital since its inception. That kind of performance tracking is only possible with precise accounting of every dollar from contribution to distribution. You can see more about their private equity fund performance history on Calpers.ca.gov.

Ultimately, the integrity of these contribution and distribution records is everything. It directly affects every partner's bottom line, builds crucial investor trust, and creates the auditable financial backbone of the entire fund.

Here is the rewritten section, designed to sound like it was written by an experienced human expert.

Valuing Assets and Calculating Net Asset Value (NAV)

In the public markets, you know what a company is worth down to the second. A stock ticker tells you everything. Private equity is a completely different world; the companies a fund owns are illiquid and don't come with a daily price tag. This is where one of the most critical disciplines of private equity fund accounting comes in: the art and science of valuation.

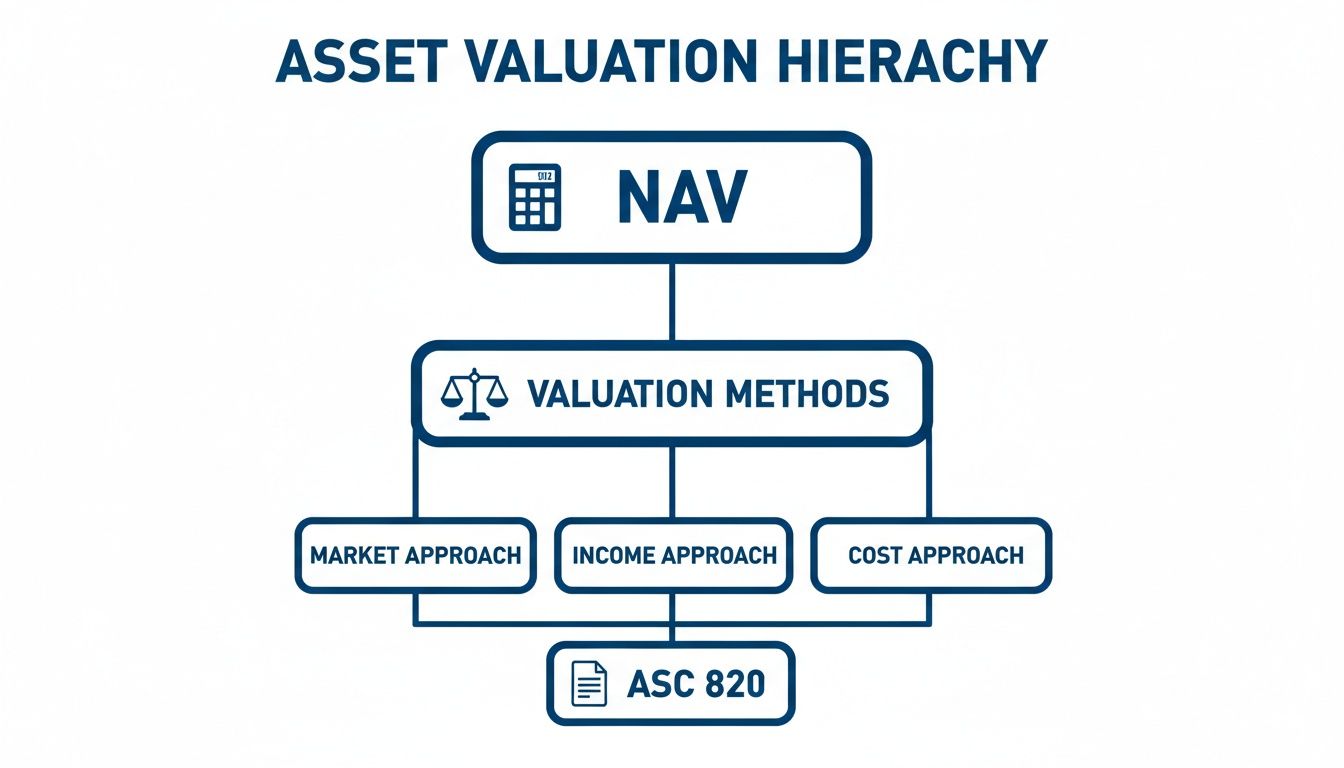

Getting the valuation right is everything. It’s the only way to truly understand a fund's health and performance. All that work boils down to one crucial metric: the Net Asset Value (NAV). The NAV is the total fair value of everything the fund owns, minus its liabilities. You can think of it as the fund's "market cap" at a given moment—the ultimate report card for LPs, the basis for the GP's fees, and the benchmark for the entire industry.

How Do You Value Something That Doesn't Have a Price?

Since you can't just look up a stock price, fund accountants rely on a set of established methodologies to estimate what a private company is worth. This isn't just guesswork; the process is guided by strict accounting principles, namely ASC 820 (Fair Value Measurement), which creates a framework for keeping valuations consistent and transparent. Rarely is one method used alone. The real skill lies in blending several approaches to arrive at a value you can stand behind.

Here are the workhorses of private equity valuation:

Comparable Company Analysis (CCA): This is a market-based approach. You look at publicly traded companies in the same industry, of a similar size, and with a similar business model. By analyzing their valuation multiples—like how their enterprise value compares to their EBITDA—you can apply a similar yardstick to your private company.

Discounted Cash Flow (DCF): This method looks inward, focusing purely on the company's ability to generate cash. You project the company's future cash flows for the next 5-10 years and then discount those future dollars back to what they're worth today. It’s a fundamental, bottom-up view of value.

Precedent Transaction Analysis: Here, you're essentially looking for a receipt. You study recent M&A deals where similar private companies were bought or sold. The prices paid in those transactions are a powerful signal of what your portfolio company could be worth in the current market.

Imagine a fund holds a fast-growing tech startup that isn't profitable yet. A DCF model would be a shot in the dark because its future cash flows are anyone's guess. In that case, an experienced accountant would lean heavily on what similar public tech companies are trading at and what bidders have paid for comparable startups recently.

The Judgment Call in Valuing Illiquid Assets

Let's be clear: valuing private assets is as much an art as it is a science. Without a live market price, subjectivity is unavoidable. This is where sound judgment, deep industry experience, and meticulous documentation become your best friends.

The real challenge is the lack of "observable inputs." You're working with assumptions about growth, market shifts, and future performance—all of which are moving targets. This is precisely why a framework like ASC 820 is so essential. It forces a disciplined, evidence-based process on a task that is fundamentally uncertain.

These valuations are not just for internal bookkeeping. They have a direct and powerful impact on the fund's reported performance and are put under a microscope by auditors and investors. A big write-up or write-down in just one company can swing the fund’s NAV dramatically, which in turn affects carried interest payouts and an LP’s confidence in the GP.

The market itself constantly reminds us of this. In 2025, global private equity exits hit an incredible $1.3 trillion in value—a 41% jump from the year before. That surge, driven by a wave of PE-backed IPOs, dumped a ton of fresh data into the market. Suddenly, fund accountants had a new set of public comps to reconcile against their private valuations, highlighting just how dynamic this process truly is. You can see more on these trends in the latest Global Private Markets report from Mcksey. It’s a perfect example of how private valuations don't exist in a vacuum; they're constantly interacting with the realities of the public markets.

Understanding Fees, Carried Interest, and Waterfall Models

In private equity, splitting the profits is a far cry from a simple 50/50 division. It’s a highly structured process governed by a critical document: the fund’s Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA). This is the rulebook that spells out exactly how the General Partner (GP) gets paid for their work and how investors (the Limited Partners, or LPs) get their money back—and hopefully, a lot more.

This intricate system is built on management fees, a performance bonus called carried interest, and a payout sequence known as the waterfall model. For anyone involved in a private equity fund, getting a firm handle on these concepts is non-negotiable. They are the engine that aligns the GP's incentives with the LPs' financial goals.

The Two Types of GP Compensation

A GP’s compensation is designed to reward them for both the daily grind of managing the fund and the long-term success of its investments. It breaks down into two main components.

Management Fees: Think of this as the GP's salary for running the show. These are predictable, regular payments from the LPs to the GP, typically around 2% of the fund's committed capital annually. These fees cover the essential operating costs—salaries for the investment team, office space, travel, and all the due diligence required to find and vet potential deals.

Carried Interest: This is the big prize—the performance incentive. Often called "carry," it’s the GP's share of the fund's profits. But here’s the key: it only kicks in after the LPs have gotten their initial investment back, plus a predetermined minimum return. This share is typically 20% of the profits, which gives us the famous "2 and 20" model.

The diagram below shows how these financial mechanics are built on a solid foundation of asset valuation. Accurate valuation is what makes the whole system work, from calculating the fund's performance to determining the final carry.

This structure ensures the fund's Net Asset Value (NAV) is calculated properly under accepted accounting standards like ASC 820, providing the official basis for profit distributions.

Decoding the Distribution Waterfall

The distribution waterfall is the core mechanism in private equity fund accounting that dictates the precise order in which cash gets paid out. The best analogy is filling a series of buckets, one after the other. You can't start filling the second bucket until the first one is completely full.

This tiered system ensures everyone gets paid in a logical, fair sequence, with investors first in line.

A typical distribution waterfall has four main tiers, or "buckets," that must be filled in sequential order. This structure protects the LPs by ensuring their capital and preferred return are prioritized before the GP shares in the upside.

Let's walk through the four common tiers:

Return of Capital: 100% of all distributions go straight to the LPs until they've received back every single dollar they originally invested.

Preferred Return: After the LPs are whole on their capital, they continue to receive 100% of distributions until they hit a specific minimum return, known as the hurdle rate. This is often set around 8% per year.

GP Catch-Up: Now it's the GP's turn. Once the LPs have their capital and preferred return, 100% of the cash flow is directed to the GP until they have "caught up" by receiving a specific share (e.g., 20%) of all profits distributed to date.

Final Split (Carried Interest): With all prior tiers satisfied, the remaining money is split. Typically, 80% goes to the LPs, and the final 20% goes to the GP. This 20% is their carried interest.

Tracking these distributions requires meticulous accounting. It’s no surprise, then, that private equity’s influence is reshaping the accounting industry itself. Deal trackers counted 147 private equity buyouts of CPA and accounting firms between 2020 and 2026, creating an estimated $200 billion in new enterprise value. For investors, this trend means more accounting partners now have firsthand expertise in the complex fund mechanics they need. You can read more about the PE-backed accounting firm trend on cpatrendlines.com.

American vs. European Waterfalls

Not all waterfalls are built the same. The timing of the GP's payout hinges on whether the fund uses an American or a European model, and the difference is crucial for LPs.

American Waterfall (Deal-by-Deal): The waterfall calculation is run for each investment individually. This lets the GP take carry from early winners, even if other deals in the portfolio are struggling.

European Waterfall (Whole-Fund): The waterfall is applied at the total fund level. Here, the GP only sees a dime of carry after all LP capital across all deals has been returned, plus the preferred return. It’s a much more LP-friendly approach.

The table below breaks down the key differences.

American vs European Waterfall Models Compared

| Feature | American Waterfall (Deal-by-Deal) | European Waterfall (Whole-Fund) |

|---|---|---|

| Calculation Basis | Each individual investment is treated as its own waterfall. | The entire fund's portfolio performance is aggregated. |

| GP Payout Timing | Earlier. GPs can receive carry as soon as a single deal is exited profitably. | Later. GPs must wait until the entire fund clears the hurdle. |

| Risk to LPs | Higher. GPs could be overpaid early if later deals underperform. | Lower. Protects LPs' total return before the GP gets paid. |

| Clawback Provision | Essential. Almost always includes a clawback to reclaim overpayments. | Less critical, but still common as a safeguard. |

Because the American model introduces the risk of the GP getting paid too much, too soon, most of these agreements include a clawback provision. This is a contractual obligation forcing the GP to return any excess carry they received if, by the end of the fund's life, the total returns don't justify the performance fees they were paid.

Managing Tax Compliance and Investor Reporting

Beyond the deal-making and number-crunching, a huge part of private equity fund accounting revolves around managing the tangled web of tax compliance and investor reporting. These aren't just back-office chores; they are fundamental to maintaining trust with Limited Partners (LPs) and staying on the right side of regulators. A fund’s reputation hinges not just on its Internal Rate of Return (IRR), but on its ability to deliver clear, timely, and accurate financial information.

The real challenge comes from the way private equity funds are built. Most are structured as limited partnerships, which act as pass-through entities. This means the fund itself doesn't pay corporate income tax. Instead, all the profits, losses, and other tax items flow directly to the investors. This setup demands a completely different approach to accounting than what you’d find in a typical corporation.

GAAP vs. Tax Accounting: The Two Sets of Books

A core complexity in fund administration is the constant need to maintain two parallel sets of financial records: one for investors and one for the tax authorities. They tell different stories for different audiences.

- GAAP Accounting: This is the language of investor reporting, guided by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. Its job is to paint a picture of the fund's economic health and fair market value, with the Net Asset Value (NAV) as the headline number.

- Tax Accounting: This is what the IRS cares about. It follows the Internal Revenue Code and is solely focused on calculating the taxable income that gets allocated to each investor.

The differences between the two can be stark. For instance, GAAP might value an asset at its current market price, while tax rules insist on using its original cost basis. The fund accountant’s job is to meticulously track both realities to ensure investors get accurate financial statements and the right information for their tax returns.

The All-Important Schedule K-1

For any LP, the Schedule K-1 is one of the most critical documents they’ll receive all year. This is the IRS form that breaks down their specific share of the fund's income, deductions, and credits. It's the key they need to file their own taxes.

Issuing K-1s on time and without errors is a non-negotiable part of a General Partner’s (GP’s) fiduciary duty. Delays or mistakes can cause a major headache for LPs, forcing them to amend personal tax returns and quickly eroding the GP-LP relationship.

This is where precise accounting becomes absolutely crucial. Every single transaction—from a capital call at the start to a final distribution years later—has to be allocated perfectly to each partner’s capital account. If not, the K-1s will be wrong.

Navigating Key Tax Complexities

The K-1 is just the start. Fund accountants constantly wrestle with other complex tax issues that have a direct impact on investors, especially institutional and tax-exempt LPs. Two of the biggest hurdles are UBTI and SALT.

- Unrelated Business Taxable Income (UBTI): This is a potential trap for tax-exempt investors like university endowments or charitable foundations. If the fund generates income from debt-financed investments or directly operates a business, these LPs can suddenly face an unexpected tax bill. Accountants have to carefully track and report UBTI to prevent these nasty surprises.

- State and Local Tax (SALT) Compliance: When a fund invests in companies all over the country, it creates a messy tax footprint. This can trigger filing requirements for both the fund and its LPs in multiple states, creating a massive compliance burden that needs to be managed proactively.

Upholding ILPA Reporting Standards

To bring some order to the chaos, many institutional investors now expect funds to follow the best practices laid out by the Institutional Limited Partners Association (ILPA). The ILPA Reporting Template offers a standardized format for everything from financial statements to fee disclosures.

Adopting these standards isn't just about checking a box. It helps LPs more easily compare performance across different funds and gives them a much clearer window into how their capital is being managed. For a fund manager, following ILPA guidelines is a powerful signal of transparency that can be a real advantage when it's time to raise the next fund. It simply ensures everyone is speaking the same financial language.

Common Questions About Private Equity Fund Accounting

When you're dealing with private equity, you're bound to run into some unique accounting questions. The rules are just different from what you see in the public markets. Here are straightforward answers to a few of the questions we hear most often from both fund managers and investors.

Fund Accounting vs. Corporate Accounting: What's the Real Difference?

While they both involve tracking money, they’re playing two completely different games. Think of corporate accounting as taking a snapshot of a single, operational business. Its main job is to report on profitability and financial health for shareholders, using familiar metrics like revenue and net income, usually on a quarterly basis.

Private equity fund accounting, on the other hand, is all about managing an investment partnership. Its world revolves around tracking capital as it moves between the General Partner (GP) and the Limited Partners (LPs). Instead of revenue, the key metrics are things like Net Asset Value (NAV), Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and Distributions to Paid-In Capital (DPI). The entire process is dictated by a specific legal document—the partnership agreement—not just standard corporate reporting rules.

How Often Is a Fund's NAV Actually Calculated?

In the private equity world, Net Asset Value (NAV) is almost always calculated on a quarterly basis. This schedule lines up perfectly with the investor reporting cycle, giving LPs a consistent and formal update on how the fund is doing and what their investment is worth.

You can't just get a real-time price for a private company like you can with a public stock. Valuing these illiquid assets is a hands-on, analytical process. That makes trying to calculate NAV daily or weekly both impractical and frankly, unnecessary for investments designed to be held for years.

The quarterly NAV is more than just a number; it's the bedrock of the fund's operations. It's the official valuation used to calculate management fees, report performance, and figure out how much carried interest has been earned (but not yet paid).

What Happens If an Investor Fails to Fund a Capital Call?

When a Limited Partner (LP) doesn't pay up on a capital call, it’s known as a default. This is a big deal, and the fund’s Limited Partnership Agreement (LPA) has very specific, and often harsh, consequences built in to handle it. The GP has a few tools at their disposal to protect the fund and the other investors.

Some of the most common remedies for a default include:

- Charging steep penalty interest on the amount that's overdue.

- Forcing the defaulting partner to forfeit their interest in the fund, often at a significant discount to its actual value.

- Selling the defaulting partner's stake to the other LPs or even an outside party.

- Preventing the LP from participating in any new investments, which effectively waters down their stake in the fund's future upside.

These penalties are intentionally severe. The fund’s success depends on the GP being able to call on committed capital when a great investment opportunity arises, and these rules ensure everyone holds up their end of the bargain.

Why Are Clawback Provisions So Important?

A clawback provision is an essential safety net for investors, especially in funds that pay out profits on a deal-by-deal basis (an American waterfall). It protects LPs from a situation where a GP gets paid a lot of carried interest on a few early wins, only for the rest of the fund’s investments to fizzle out later.

Without a clawback, a GP could collect huge performance fees in the first few years. But if the fund’s overall performance ends up being just average, the GP could walk away with much more than their agreed-upon 20% of the profits.

The clawback clause is a contractual guarantee that forces the GP to return any of that excess carry to the investors. It’s the mechanism that ensures, by the time the fund is fully liquidated, the profit split truly reflects the 80/20 arrangement laid out in the LPA. Ultimately, it’s a critical tool for making sure the GP's and LPs' interests stay aligned for the entire life of the fund.

At Blue Sage Tax & Accounting Inc., we specialize in demystifying the financial complexities faced by investors, family offices, and closely held businesses in New York City. From navigating partnership tax structures to ensuring compliance across multi-state investments, our team provides the clarity and strategic insight you need. If you require expert guidance on your private equity investments or other complex financial matters, let's connect.

Discover how we can help you achieve your financial goals by visiting us at https://bluesage.tax.