Selling a valuable asset often brings a significant tax bill, but what if you could spread that liability over time, paying tax only as you receive the money? That's the core idea behind an installment sale, a powerful tax-deferral strategy governed by IRC Section 453.

Instead of getting hit with a single, massive tax bill in the year of the sale, an installment sale lets you recognize the gain proportionally over several years. This method aligns your tax payments with your actual cash flow from the sale. In fact, for qualifying sales, this is the default tax treatment—you have to actively opt out if you want to pay all the tax upfront.

The Foundation of Tax Deferral

Think about selling a piece of investment property or a family business you've built from the ground up. If you let the buyer pay you over five or ten years, the installment method ensures you're not paying tax on money you haven't even received yet. This simple, common-sense principle prevents a major cash crunch and gives you tremendous control over your financial planning.

By spreading the taxable gain across multiple years, you can often avoid getting bumped into a higher tax bracket. This income-smoothing effect can dramatically lower your total tax bill over the life of the note. The benefits are practical and immediate:

- Better Cash Flow: Your tax payments are tied directly to the cash you receive from the buyer.

- Smarter Tax Bracket Management: Spreading the income can help you stay in a lower marginal tax bracket each year.

- A More Attractive Deal: Offering seller financing can make your asset more appealing to a wider range of buyers who might not qualify for traditional financing or have the capital for an all-cash offer.

A Brief History of Installment Sales

The modern rules we use today were locked in when IRC Section 453 was enacted in 1980. Before that, sellers could face the nightmare of paying the full tax on their gain immediately, even if they were only getting a small down payment. This legislative change was a lifeline for real estate investors and business owners.

The proof is in the numbers. Real estate installment sales jumped by 15% between 2015 and 2022. During that period, we saw over 120,000 such deals reported, with sellers deferring an average gain of $450,000. If you're looking for more background on how this works in practice, the team at Porte Brown has some great insights.

At its heart, the installment method transforms a potentially overwhelming tax event into a manageable, multi-year financial strategy. It’s about matching tax obligations to economic reality—paying tax on profit when you actually have the cash in hand.

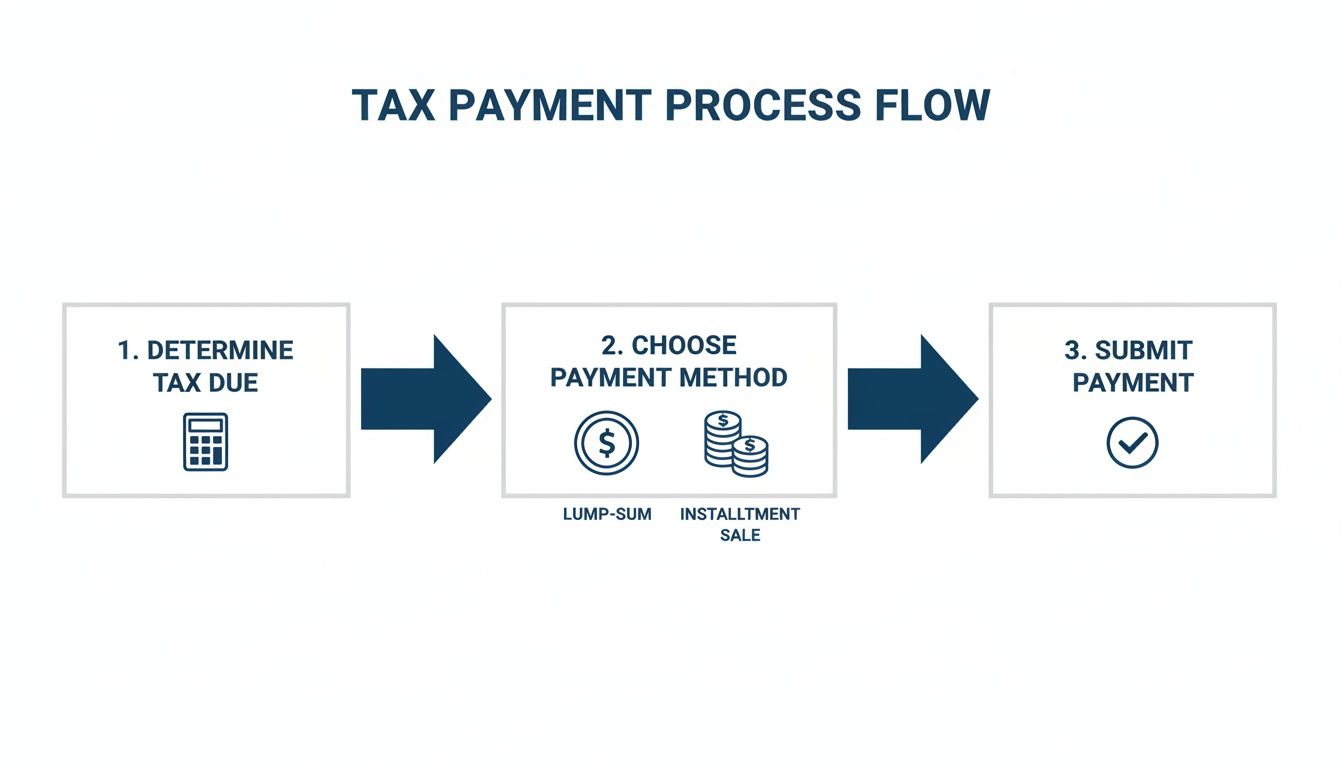

Let's quickly compare this approach to a traditional sale where you get all your money at once.

Installment Sale vs Lump-Sum Sale At a Glance

The table below breaks down the fundamental differences in how a sale is treated for tax purposes when you receive the money all at once versus over time.

| Attribute | Lump-Sum Sale | Installment Sale (IRC §453) |

|---|---|---|

| Tax Timing | Entire gain is taxed in the year of the sale. | Gain is taxed proportionally as payments are received over multiple years. |

| Cash Flow | Receive all proceeds at closing but must pay the full tax bill shortly after. | Tax payments are spread out, aligning them with the cash received from the buyer. |

| Tax Bracket Impact | A large, one-time gain can easily push you into a higher tax bracket. | Spreading the gain can help keep your annual income in a lower tax bracket. |

| Complexity | Simpler calculation; report the entire sale on one tax return. | Requires annual tracking and reporting on Form 6252 for the life of the note. |

This high-level view shows the clear trade-off: a lump-sum sale is simpler, but an installment sale offers powerful tax deferral and cash flow benefits.

Understanding this core concept is the first step. Before we get into the nitty-gritty of the calculations on Form 6252 or the tricky rules for things like depreciation recapture, getting this foundation right is key to structuring a smart, strategic sale. From here, we'll build on these basics and explore the mechanics you'll need to navigate.

How to Calculate and Report Your Gain on Form 6252

If you want the tax-deferral benefits of an installment sale, you can't just casually mention it on your tax return. The IRS requires a specific, detailed accounting of the transaction, and that's where IRS Form 6252, Installment Sale Income, comes in. This is the official form for tracking your sale year after year.

Think of each payment you receive from the buyer as a mix of two things: a non-taxable return of your initial investment (your basis) and your taxable profit. The whole point of Form 6252 is to give you a clear, repeatable formula to separate those two pieces for every payment.

You'll file this form for the year of the sale and then again for every single year you receive a payment. It becomes a recurring part of your tax filing—attaching to your Form 1040 if you're an individual or your business return—until the buyer makes that final payment and your full gain has been reported.

This flowchart shows the fundamental difference in timing between a lump-sum sale and an installment sale.

As you can see, the installment method breaks one giant tax bill into a series of smaller, predictable payments. This helps you manage your tax liability and align it with the cash you're actually receiving.

The Key Calculation: Gross Profit Percentage

At the heart of every installment sale calculation is one critical figure: the gross profit percentage. This number is the key that unlocks how much gain to report each year. You calculate it once, in the year of the sale, and then apply that same percentage to every principal payment you receive for the life of the loan.

The formula itself is pretty straightforward:

Gross Profit Percentage = Gross Profit / Contract Price

Let’s quickly define those terms in plain English:

- Gross Profit: This is your total gain on the sale before taxes. To find it, take the selling price and subtract your adjusted basis in the property and any selling expenses you paid, like broker commissions or legal fees.

- Contract Price: This is the total amount of money the buyer is scheduled to pay you. For most simple sales, it’s just the selling price. The calculation gets a bit more complex if the buyer assumes your existing mortgage, which would reduce the contract price.

Once you have this percentage, the math is simple. Just multiply it by the principal portion of the payments you received during the year. The result is your taxable gain for that year.

A Practical Example: Selling a Commercial Building

Theory is one thing, but let's see how this works with real numbers. Imagine you're selling a commercial building you’ve held for a long time.

Sale Details:

- Selling Price: $1,000,000

- Adjusted Basis: $550,000 (your purchase price plus capital improvements, minus accumulated depreciation)

- Selling Expenses: $50,000 (realtor's commission)

- Payment Terms: A $200,000 down payment at closing, with the remaining $800,000 paid in four equal annual installments of $200,000.

First, let's figure out the total profit on the deal.

- $1,000,000 (Selling Price) – $550,000 (Adjusted Basis) – $50,000 (Selling Expenses) = $400,000 Gross Profit

Next, what's the contract price? In this case, the buyer is paying the full $1,000,000 directly to you and isn't taking over any of your loans, so the contract price is $1,000,000.

Now we can calculate our key percentage:

- $400,000 (Gross Profit) / $1,000,000 (Contract Price) = 40%

This 40% is our magic number. It tells us that for every dollar of principal the buyer pays, 40 cents is taxable gain. The other 60 cents is simply a tax-free return of our original investment.

In Year 1, you received the $200,000 down payment. To calculate your taxable gain, you'll do this:

- $200,000 (Principal Received) x 40% (Gross Profit Percentage) = $80,000 Taxable Gain

So, for Year 1, you report $80,000 of gain on Form 6252. Then, for each of the next four years, when you receive your $200,000 payment, you'll report another $80,000 of gain. It’s that consistent.

Over the full five-year term, you'll have reported a total of $400,000 in gain ($80,000 x 5 years), which perfectly matches the total gross profit we calculated at the start. The installment method didn't make the tax disappear; it just gave you a much more manageable way to pay it.

Navigating Depreciation Recapture and Interest Rules

While the installment method is a fantastic tool for deferring capital gains, it's not without its landmines. A couple of critical exceptions can easily catch sellers off guard, and ignoring them can lead to a nasty tax surprise in the year of the sale. We're talking about depreciation recapture and interest.

These aren't just minor details; they are mandatory rules that can dramatically change your tax outcome, especially in that first year.

For anyone selling a depreciable business or investment property, getting a handle on these rules is non-negotiable. Overlooking them often results in a much higher tax bill than you planned for.

The Immediate Hit of Depreciation Recapture

When you sell an asset like a building or equipment for a profit, part of that gain is often due to the depreciation deductions you've taken over the years. The IRS sees it this way: those deductions lowered your ordinary income each year, so when you sell, the government "recaptures" that benefit by taxing it as ordinary income, not as a capital gain.

This is the single biggest exception to the installment sale rules. All depreciation recapture income must be recognized in the year of the sale, no matter how little cash you've received from the buyer. You simply cannot defer this part of your gain.

Think of depreciation recapture as a "tax advance" the IRS collects immediately. The tax benefit you got from depreciation is settled upfront at the sale, before any of the capital gain deferral even starts.

This rule applies to the two main types of recapture:

- Section 1245 Recapture: This is for tangible personal property—think machinery, equipment, and company vehicles.

- Section 1250 Recapture: This one applies to real property. For real estate, a portion of the gain known as "unrecaptured Section 1250 gain" is taxed at a maximum federal rate of 25%.

The bottom line? Your first-year tax bill from an installment sale can be surprisingly large, even if you only received a small down payment. That's because all this recaptured ordinary income hits your tax return at once.

Why Interest Is Non-Negotiable

The second major rule to watch out for involves interest. When you let a buyer pay you over time, you're essentially acting as their bank. The tax code demands that a portion of the payments you receive must be treated as interest, which is always taxed as ordinary income.

You can't sidestep this by creating a 0% interest loan. If your installment agreement doesn't include a reasonable interest rate, the IRS will step in and "impute" one for you using the Applicable Federal Rates (AFRs). These are the minimum interest rates the IRS publishes every month.

This is often called the unstated interest rule. It effectively reclassifies part of what you thought were principal payments (a mix of tax-free basis and capital gain) into fully taxable ordinary interest income. This can easily lead to a higher tax bill, since ordinary income tax rates are typically much higher than long-term capital gain rates.

Key Interest Rules to Remember:

- State an Adequate Rate: Always write a fair, stated interest rate into your sale agreement. A good rule of thumb is to use a rate at least as high as the AFR for the month you close the deal.

- Report Interest Annually: You must report interest income each year as you receive it (or as it accrues, depending on your accounting method). This is handled separately from the capital gain on your tax return.

- AFRs Vary by Term: The IRS has different AFRs for short-term (up to 3 years), mid-term (3 to 9 years), and long-term (over 9 years) notes. Make sure you use the right one.

Failing to properly structure the interest on your sale is a common and costly mistake. It doesn't just trigger unexpected taxes; it can also create compliance headaches. Proper planning is the only way to ensure the installment sale tax treatment aligns with your goals and stops the IRS from rewriting the terms of your deal for you.

Special Rules for Related Party Sales

While the installment method is a powerful tax-deferral tool, the IRS keeps a close eye on sales between related parties. The government put these special rules in place to stop a specific kind of loophole: families or controlled businesses using an installment sale to get all the cash from an asset now while pushing the tax bill far into the future.

Think about this common scenario. You sell a rental property to your son on a 15-year installment note, planning to recognize the gain slowly over time. But just a few months later, your son turns around and sells that same property to an unrelated buyer for a single lump-sum cash payment.

From the IRS's perspective, your family unit has effectively "cashed out" on the property. The money is in the family, yet you're still deferring the tax liability. This is exactly what the related-party rules are designed to prevent.

The "Second Disposition Rule" Explained

To clamp down on this strategy, the tax code has a provision often called the "second disposition rule." It’s a critical anti-abuse trigger you need to understand.

Here’s how it works: If you sell property to a "related person" on an installment plan, and that person resells it within two years, the rule can force you to recognize your deferred gain immediately. Your careful tax planning goes right out the window.

In the year of that second sale, you’ll have to report the rest of your original gain. The IRS essentially treats the cash your relative received from the second sale as if it were paid directly to you, wiping out the deferral benefit of your installment agreement.

The two-year rule is a bright-line test. Its entire purpose is to ensure that the tax deferral benefit is used for genuine financing arrangements, not as a short-term trick for related parties to get cash out of an asset tax-free.

Who Counts as a Related Party?

The definition of a “related party” under these rules is broader than you might think. It’s not just about your immediate family. The IRS considers the following to be related parties:

- Family Members: Spouses, children, grandchildren, parents, and even siblings.

- Controlled Entities: Any corporation or partnership where you hold more than 50% of the value or ownership interest.

- Trusts and Fiduciaries: A web of trust and estate relationships also falls under these rules.

This is a huge deal for business owners and high-net-worth families. A sale to a C-Corp you control is viewed no differently than a sale to your daughter.

Are There Any Exceptions?

Thankfully, the rule isn't absolute. Not every resale within two years will trigger this painful gain acceleration. The IRS carves out a few important exceptions. The big one is if you can prove to the IRS that tax avoidance wasn't one of the main reasons for either the initial sale or the subsequent resale.

Other key exceptions include:

- A sale of stock back to the company that issued it.

- An involuntary conversion, like if the property is destroyed in a fire or taken by eminent domain.

- Any resale that happens after the death of either you (the original seller) or the related person who bought it from you.

These rules add a serious layer of complexity, especially for family business succession and estate planning. Before you even think about structuring an installment sale with a relative, you have to be crystal clear on their intentions for the property. Otherwise, you could be in for a very nasty, and very expensive, tax surprise.

Strategic Planning: When to Elect Out of the Installment Method

The installment method is the default for a reason—deferring tax is almost always a powerful move. But "default" shouldn't be mistaken for "mandatory." In some cases, the smartest tax strategy is to do the exact opposite: elect out of the installment method and recognize the entire gain in the year of the sale.

It might sound counterintuitive to intentionally accelerate a tax bill. Why pay now what you can put off until later? But in the right circumstances, this is a sophisticated play—a classic case of taking a short-term hit for a much better long-term financial outcome. This isn't a decision to be made lightly; it requires looking at your entire financial landscape, not just this one transaction.

Keep in mind, once you elect out, there's no turning back. The decision is permanent and binding for that specific sale. You have to make the call by the due date (including extensions) of the tax return for the year the sale took place.

Why Would Anyone Forgo Tax Deferral?

Choosing to recognize your gain upfront is never an accident; it's a strategic maneuver. It’s about timing your income recognition to perfectly align with other things happening in your financial life. This is where high-net-worth individuals and savvy business owners can really use the tax code to their advantage.

Here are the most common situations where taking the immediate tax hit makes perfect sense:

- To Soak Up Capital Losses: Let's say you're sitting on significant capital loss carryforwards from previous years. A large capital gain from your sale can act like a sponge, absorbing those losses. You effectively neutralize the tax on your gain while finally getting some value from old losses that might otherwise expire.

- Anticipating Higher Tax Rates in the Future: Tax laws are anything but static. If you have good reason to believe that capital gains rates are on the rise, paying the tax at today's known rate could be far cheaper than deferring the gain into an uncertain, higher-tax future.

- Expecting a Jump into a Higher Tax Bracket: Maybe a new business is about to take off, or you're expecting a windfall from another investment. Recognizing the gain now, while you're in a lower tax bracket, could lead to a much smaller overall tax bill than if you spread the payments out over future years when your income is higher.

Electing out transforms a tax event into a financial tool. It’s a deliberate choice to accelerate a tax liability to create a better long-term outcome, such as turning dormant capital losses into immediate tax savings.

The Decision is Final

Making the election is procedurally simple—you just report the full gain on Schedule D and Form 8949 instead of filing Form 6252. The consequences, however, are major and irreversible. The IRS is notoriously strict about this; they rarely grant permission to revoke the election unless you can prove you received blatantly incorrect advice from a tax professional.

This finality is precisely why a thorough analysis is so critical. Before you pull the trigger, you need to model the tax impact both ways. You have to weigh the time value of money—the benefit of keeping that tax payment invested and working for you—against the potential savings of recognizing the gain all at once. A good tax projection will lay out the numbers and make the best path clear.

Aligning the Sale with Your Long-Term Goals

Ultimately, the choice to use the installment method or elect out can't be made in a vacuum. It has to fit into your bigger financial and estate planning picture.

For example, if your primary goal is wealth transfer, an installment sale to a family trust could be a perfect fit. On the other hand, if you're simplifying your finances for retirement and happen to have a pile of losses to use, electing out offers a clean and efficient solution. For any business owner or real estate investor, a well-planned sale is a cornerstone of a sound financial strategy, and the experts at firms like Blue Sage Tax & Accounting can help model these complex scenarios. The right installment sale tax treatment depends entirely on your unique circumstances and long-term vision.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid in Installment Sales

Structuring an installment sale can be a brilliant tax-deferral move, but it's not without its landmines. A simple misstep in the fine print can unravel the whole strategy, leading to some nasty surprises from the IRS. Getting ahead of the most common errors is the key to making sure your sale works for you, not against you.

These mistakes usually pop up when sellers misunderstand a specific rule or just plain overlook an obligation. From depreciation recapture to hidden interest rules, let's walk through the traps that can accelerate your tax bill and throw your financial planning into chaos.

Forgetting About Depreciation Recapture

This is the big one. By far, the most frequent and painful mistake is failing to deal with depreciation recapture. Many sellers think their entire gain gets spread out over the payment period. That's a dangerous assumption. The IRS is crystal clear on this: all gain attributable to depreciation recapture must be reported as ordinary income in the year of the sale.

There's no getting around it. Even if you only get 1% down, you owe tax on 100% of the recaptured depreciation right away. Missing this detail can leave you with a massive, unplanned tax bill in year one.

Setting an Inadequate Interest Rate

Another classic mistake is drawing up a note with a 0% interest rate or one that's clearly below market. The IRS looks at an installment sale as a financing deal, and they expect to see interest. If you don't state an adequate interest rate, they'll step in and create one for you using the Applicable Federal Rates (AFRs).

This is called the "imputed interest" rule, and it’s bad news for your tax return. It recharacterizes part of your principal payments as ordinary interest income, which gets taxed at much higher rates than long-term capital gains. A properly structured note with a fair, stated interest rate is non-negotiable.

Misunderstanding the Pledge Rule

The "pledge rule" is a sneakier pitfall, but it can be just as damaging. Let's say you take your installment note and use it as collateral to get a loan. In the eyes of the IRS, those loan proceeds are now considered a payment on the note. This immediately triggers recognition of your deferred gain, up to the amount you borrowed.

You can't have your cake and eat it too. The IRS won't let you defer the tax while simultaneously cashing out the note's value with a separate loan. Pledging the note essentially vaporizes your tax deferral benefit on the spot.

A Quick Guide to Staying Out of Trouble

These aren't the only potential stumbles, but they are the most common. Keeping them in mind during the planning phase is crucial for a successful installment sale.

Here’s a quick summary of frequent mistakes and how to steer clear of them.

Common Installment Sale Errors and Corrections

| Common Pitfall | The Consequence | How to Avoid It |

|---|---|---|

| Ignoring Depreciation Recapture | A large, unexpected ordinary income tax bill in the year of the sale. | Calculate and report all recapture income on your year-one tax return. Plan for the tax payment. |

| Failing to Charge Interest | The IRS imputes interest, converting capital gains into higher-taxed ordinary income. | Include an interest rate in your agreement that is at least equal to the current AFR. |

| Using the Note as Collateral | Immediate taxation of your deferred gain under the "pledge rule." | Do not pledge the installment obligation as security for any other loan. |

| Violating Related-Party Rules | A quick resale by a related buyer can trigger your entire deferred gain. | Understand the two-year rule and ensure the second disposition is not planned to avoid taxes. |

Getting the tax treatment right is everything in an installment sale. With some smart, proactive planning and a sharp eye for these common traps, you can confidently use this strategy to hit your financial goals without inviting trouble from the IRS.

Frequently Asked Questions

When you start digging into installment sales, a lot of specific "what-if" scenarios pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common questions clients ask about navigating these rules.

What Kinds of Property Can't Be Sold Using the Installment Method?

Not every sale can be structured this way. Before you get too far down the road, it's critical to know that the IRS has put a few key types of property off-limits for installment sale treatment.

The main ones to watch out for are:

- Inventory: If you sell something as part of your regular business operations (like a developer selling lots in a subdivision), you can't use the installment method. This is for assets, not everyday business sales.

- Publicly Traded Securities: Selling stocks, bonds, or other securities traded on an established market won't work. The logic is that these are highly liquid, so the gain must be recognized right away.

- Sales at a Loss: This one's simple—the installment method is only for deferring gains. If you sell an asset for a loss, you have to recognize that entire capital loss in the year the sale happens.

Knowing these disqualifiers upfront can save you a world of headache and potential IRS trouble.

Can I Structure an Installment Sale with a Family Member?

This is where things get tricky, and for good reason. The short answer is usually no, at least not for depreciable property sold between related parties (think spouses, children, or controlled businesses).

The tax code has built-in guardrails to stop people from gaming the system. Imagine selling a rental property to your son. He could start taking depreciation deductions on a new, higher basis right away, while you defer paying tax on the gain for years. To prevent this, the rules basically force you to recognize the entire gain in the year of the sale.

This anti-abuse provision is a big one. The IRS effectively treats it as if all payments were received upfront, wiping out the tax deferral benefit you were hoping for.

What If My Buyer Stops Paying?

A buyer default is a messy situation, and unfortunately, it creates a whole new taxable event: a repossession. When you take the property back, you don't just unwind the original deal; you might have to recognize a new gain or loss.

The calculation gets complicated fast. You'll essentially compare the property's fair market value at the time you repossess it against your remaining basis in the installment note. Whether that results in a capital or ordinary gain (or loss) depends on what the original asset was. The rules for repossessing real estate are also quite different from those for personal property, so getting professional guidance here is absolutely essential.

Navigating the complexities of installment sale tax treatment requires careful planning and deep expertise. At Blue Sage Tax & Accounting Inc., we partner with high-net-worth individuals and business owners in New York City to structure sales that align with their long-term financial goals, ensuring compliance and maximizing after-tax returns. Learn how we can bring clarity to your next major transaction at https://bluesage.tax.